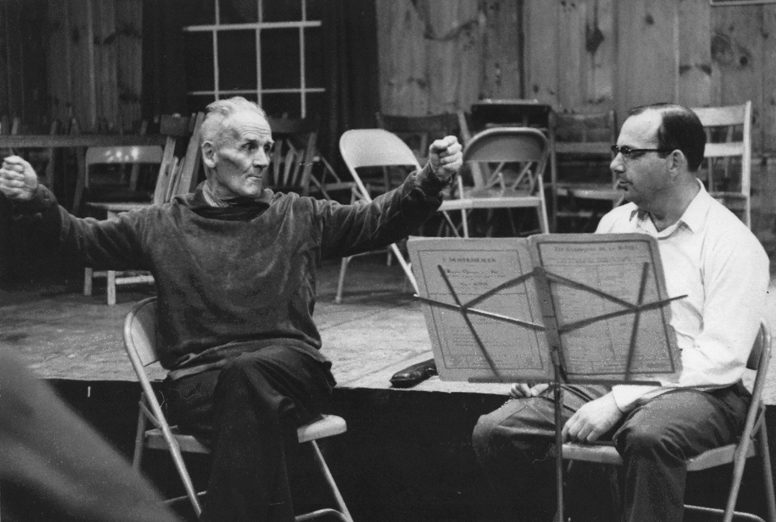

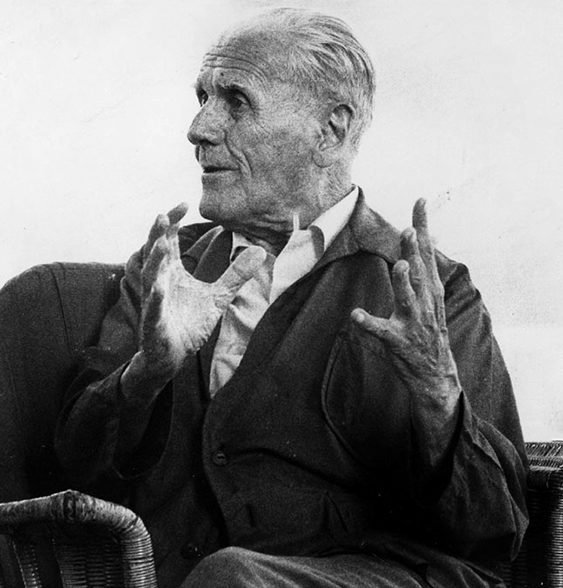

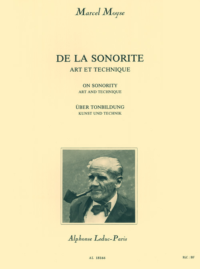

On 2 May 2014, I met with Bernard Goldberg for my second private lesson with him. Knowing that Bernie studied extensively with Marcel Moyse (1889-1984), I entered this lesson with the hope of learning more about this great French flutist and Bernie’s experiences with him. Bernie kindly obliged. Moyse’s De la sonorité was our subject. In this essay, I provide some background on Bernie’s relationship with Moyse and share a few principles that Bernie passed on to me for working with De la sonorité.

Bernie had a lifelong veneration for Marcel Moyse. While in high school, he wrote letters to Moyse, and as a young adult, he was finally able to study with the French master in person. Their intermittent work together continued up until Moyse’s passing in 1984. Given his professional stature, Bernie’s commitment to continuing his studies with Moyse is remarkable. Verne Q. Powell, the founder of Powell flutes, even once joked to Bernie, “When are you going to grow up?” in reference to this study.

Although flutists commonly refer to De la sonorité as simply that, the full title is De la sonorité: Art et technique. During my lesson, Bernie not only detailed fundamentals for playing this text but also conveyed a sense of Moyse’s artistry. He recounted a moment from the time of their first meeting:

We were on a hillside up there at Marlboro in Vermont—a beautiful sunshiny day. I just had my first class on the Handel trio sonata in C minor…

So, we just had a class and big emotion because we’d been in correspondence since I was in high school, and then came the war, and his escape and exile at his home, and I lost so many of my family. So, then we were out there in the sunshine, and he said, “The A-sharp should follow the B as smoothly and without disturbance and as openly as the sun on the earth,” he says, “as God’s love.” And, I thought to myself, “What’s this man? Who is this man who makes such a big deal about B to A-sharp?” And, over the years, I realized that here was the intensity. Not any religious belief, but the sense of beauty. What B to A-sharp, what flute playing, what music can offer to the human race. Oh, this was a guy I tell you.

The B to A-sharp here is the first pitch movement of the first exercise in De la sonorité.

From the outset of his exposition to me on De la sonorité, Bernie established that the book is a collection of exercises and that the purpose of these exercises is to develop sound. Furthermore, he contended that the flutist is to play De la sonorité without vibrato. The fact that the text is a series of exercises made it unnecessary for Moyse to state as such. Moyse drew a distinction between the vibrato of string players, which takes place outside the body, and the vibrato of flute players, which originates from within. Bernie took care to clarify that Moyse did not speak about “vibrato.” Rather, “life” in the sound was his preferred perspective. From feelings of intensity within follows life in the tone.

Bernie recommended thinking scale degrees 8 (octave of the tonic) and 7 (leading tone) when playing the first exercise in the book in order to prevent flatness through the descent. The “8” applies to the first note of each descending half-step; the “7” applies to the second note. For the ascending half-step exercise (see the top of page 9 in the text), Bernie imagined the reverse scale-degree movement, 7 to 8. In addition, he stated that Moyse encouraged the release of the upper lip upon landing on the higher note of each ascending pair of pitches. For both the descending and ascending exercises above, Bernie described the project as just letting the notes float out, a simple-sounding aim that takes some time to accomplish.

In regard to the “Attack and Slurring of Notes” exercises (see pages 15-22), Bernie made two important comments. First, he explained that as the size of the interval increases, so do the challenges of physical adjustment and intonation. Larger intervals require larger changes to one’s direction of the lips and the jaw; moreover, one’s inner hearing must be particularly discerning to ensure accurate tuning. Second, if a note fails to speak upon attack, consider the problem to be in the angle of the airstream, rather than in the use of the tongue. Bernie credited Georges Barrère for this bit of advice.

At a certain point in the lesson, Bernie asked if I understood the materials he was giving me. I laughed and replied, “Intellectually!” He was immediately sympathetic to this response. De la sonorité is a “chunk of work over the years and year and years,” as he put it.

Prescribing a course of study, he suggested working through De la sonorité, and then moving into Tone Development Through Interpretation, also by Moyse; studying the two books together is also productive. Bernie emphasized the rewards of engaging in this effort. Through intelligent practice, done with patience, the flutist can gain the resources to do whatever she wants on the instrument. “It gives you so much suppleness.”

Recognizing the enormity of these Moyse projects, I will close with one additional piece of wisdom from Bernie. It is not something I ever heard him say aloud, but it is something his words revealed.

As I mentioned in Part 1, I had the opportunity to observe Bernie teach in various settings. On his tours, we would often chat during the downtime between his commitments. The topics of conversation were wide-ranging. Sometimes, he would choose a specific student he taught that day as his subject.

Whenever Bernie spoke about students he instructed that day, he focused on what materials they could practice in order to improve some aspect of their playing. In other words, he had assessed the current capabilities and was looking ahead to what a student could accomplish as a logical next step. He did not speak in terms of who played the “best” and who did not. He did not question anyone’s potential to expand technique and artistry. He viewed it all so simply and objectively. Practice done with the proper knowledge and approach yields growth in time. This possibility is available to everyone.

Be it Moyse exercises or some other endeavor, it does not matter where we currently are in our level of skill. All we need to do is start the process of learning and maintain our commitment to it.