Re: Instrument He Knew

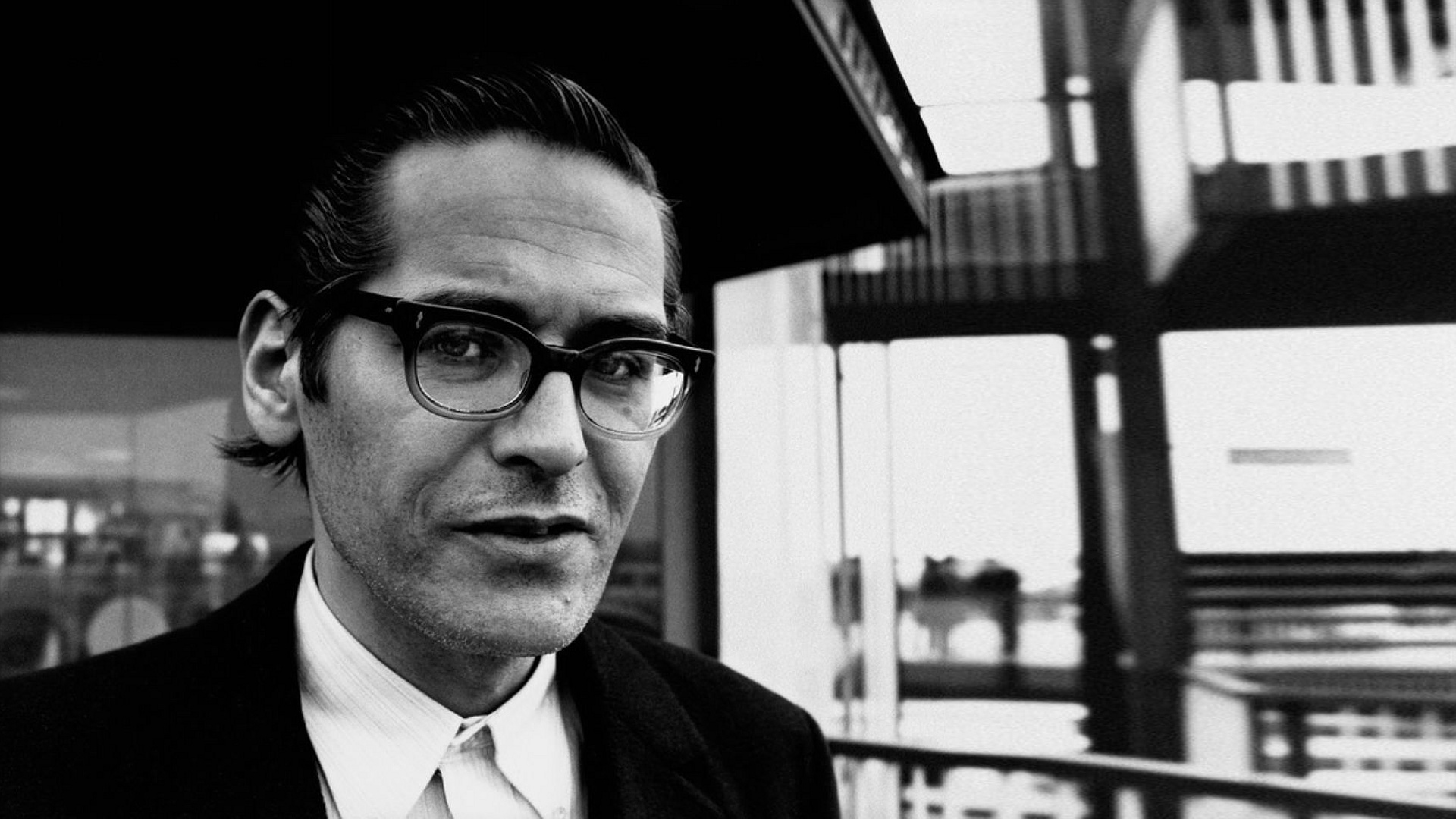

A jazz pianist’s connections to the flute and Chicago, and why I think everybody can dig Bill Evans

By Jennifer Wilhelms

It’s more the mind “that thinks jazz” than the instrument “that plays jazz” which interests me.

—Bill Evans

Since my first encounter with the Miles Davis album Kind of Blue, I have admired the piano playing of Bill Evans. His beautiful sound, depth of expression, and perfect sense for sparseness and subtlety all stir the imagination. During a recent attempt to transcribe one of his improvisations, I felt compelled to research more about his life. Study of the written and spoken words of Bill Evans reveals a profound musical mind. His philosophies on what music making is and how to approach skill building can enrich the practice of all musicians, regardless of stylistic background. Much to my surprise, I also learned that he once played the flute, and temporarily resided not far from Chicago. In this brief article, I provide an introduction to this legendary jazz pianist and sketch a sense of his artistic wisdom.

Very Early

Bill Evans (1929-1980) grew up in Plainfield, New Jersey. He began classical piano lessons at age six. Around twelve, he heard jazz for the first time. Playing in small-group settings and bands followed. Continuing his classical study, he attended Southeastern Louisiana College, where he earned two bachelor’s degrees, in piano and in music education, in 1950. Although he ultimately dedicated himself to a career in jazz, working in the classical idiom was apparently still a possibility as he prepared for professional life. After moving to New York City in 1955, he attended Mannes College for three semesters of composition study.

Like many skilled musicians, Evans had experience playing more than one instrument. Starting at age seven, he played violin for a time. By high school he had taken up the flute and piccolo, and during his studies at Southeastern Louisiana, he was first flute in the concert band. Later, Evans was stationed at Fort Sheridan, north of Chicago, while serving in the army during the Korean War. Though he played flute and piccolo in the Fifth Army Band, he continued to develop his jazz piano chops, venturing into the city to play in the clubs when off duty. Evans’s military service also led to his acquaintance with composer Earl Zindars, who was from Chicago. A graduate of Northwestern and DePaul, Zindars wrote two tunes that figured prominently in Evans’s repertoire, “Elsa” and “How My Heart Sings.” Both Zindars and Bill Scott, another friend from the army years, heard Evans play jazz on the flute, including the music of Charlie Parker, which is no small feat.

An aspect of Evans’s piano playing that is particularly lauded is its tone. Jazz writer Gene Lees praised Evans’s tone for its breadth of color and speculated that the experience of playing the flute somehow influenced Evans’s conception of his piano sound. On the other hand, Evans biographer Peter Pettinger suggested that the practice of sustaining a sound on the violin may have influenced Evans’s desire to “sing” on the piano. Perhaps this “singing” may be traced to the flute as well—a wind instrument, after all. Of course, I may be biased here, considering my attachment to the flute.

One of the gems of the flute repertoire can be found within Evans’s discography. Though the title “Valse” is misleading, an arrangement of the siciliana from J.S. Bach’s E-flat major flute sonata appears on the album Bill Evans Trio with Symphony Orchestra. During his career, Evans played with some notable jazz flutists, including Herbie Mann and Eric Dolphy. Nonetheless, he is best known for his work with his own trio, and for his collaboration with Miles Davis.

Kind of Blue

Bill Evans wrote the liner notes for the original release of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue album (1959). In his opening remarks, he describes a process of Japanese art, which he relates to improvisation in jazz:

There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

This paragraph provides a compelling introduction not only to the best-selling jazz album of all time, but also to what was perhaps Bill Evans’s primary artistic objective—the instantaneous, unhindered transmission of his internal vision. Making inner clarity external via physical action that is the epitome of ease and simplicity. Analyzing the core values of the Japanese practice, Evans points to a “conviction that direct deed is the most meaningful reflection.” This directness and meaningfulness, seen in light of the aforementioned concern with internal to external communication, illuminate what is commonly called an honest performance—any artistic act in which the combined strengths of creative vision and physical skill permit the audience to truly “see” the performer.

Universal Mind

Seven years after Kind of Blue, Bill and his brother Harry Evans, who at the time was a music educator in Louisiana, sat down in conversation for the film The Universal Mind of Bill Evans (1966). As in his Japanese art comparison, Bill Evans’s attraction to in-the-moment expression is evident. He describes jazz as “not so much a style as a process of making music…making one minute’s music in one minute’s time.” He does not restrict spontaneity to jazz improvisation, however. Rather, he argues that in all styles, composition, and performance, great music making should aim to exude a spontaneous quality.

During one segment of the film, Harry establishes an opposition between the “intrinsic value of a field” and “end results.” This remark points to an essential truth that Bill does not state directly. For him, it seems, the goal was not executing music itself, but rather, achieving freedom of expression via an artistic medium, which in his case was the piano. The fundamental problem, as Bill explains, is making technique subconscious so that one can be a spontaneous creator at the instrument. Fortunately, he articulates an approach to musical skill building. Bill’s impassioned and emphatic speaking is a testament to his strength of belief in his ideals. The following excerpt, though referring to improvising on a tune and its chord changes, applies equally well to practicing a fully composed piece of music:

[It is better to] work simply with the framework and honestly and really, and play something simple… [rather than] try to approximate [something more complex] in a vague way…in a way which is so general that [one] can’t possibly build on that. If they build on that, they’re building on top of confusion and vagueness, and they can’t possibly progress. … The point is what are you satisfied with? In other words, it is better to do something simple which is real.

Bill advocates a deliberate and mindful approach to practice. A willingness to work as simply (in quality of material) and as incrementally (in rate of progress) as necessary, is essential. This is a method which gently expands all skills: aural, physical, musical, emotive. Working so as to develop clarity of inner hearing and thinking, along with ease of physical action, is paramount. The ultimate goal is playing in which a well-defined internal impetus directs well-coordinated physical action and the external musical product.

The two brothers also discuss Bill’s quest to become a working jazz musician. In what is perhaps the most touching moment of the film, Bill explains, “Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that all I must do is take care of the music, even if I do it in a closet. If I really do that, somebody’s going to come and open the door of the closet and say, ‘Hey, we’re looking for you.’” This remarkable statement makes clear Bill’s prioritization of his artistic craft. He believed he had a unique “voice.” Through commitment to his ideals of process, his personal voice would come through, and at some point, someone would recognize what he had to offer.

Time Remembered

The Kind of Blue notes and Universal Mind film show a consistency in Bill Evans’s thinking, which an anecdote from jazz pianist Kenny Werner reinforces. In a video interview, Werner recounts the one time he met Evans. The occasion was a party in celebration of Evans’s 50th birthday, which places this moment toward the end of Bill’s short life. During the party, one of the guests asked Evans what he practices. His answer: “the minimum.” To Werner, the meaning of this seemingly perplexing response was clear. By “the minimum,” Evans meant “the minimum amount of material.” Werner argues that Evans worked on a concept until he fully absorbed it: “He practiced perfect little jewels of thought.”

Practicing the minimum resonates with the notions of simplicity, honesty, and realness that Evans espoused in The Universal Mind. In both scenarios, the message is that the musician must focus on mastering one skill or piece of material at a time. The difficulty and the quantity of the material that constitutes the minimum will vary from player to player, according to skill and experience. Musicians must call forth their highest powers of self-awareness and discipline when defining what is simple, honest, and real for themselves. Absolute ease of inner hearing, feeling, and physical execution is the starting point from which to expand.

Nardis

The Kind of Blue notes, Universal Mind film, and Werner anecdote provide a glimpse into Bill Evans’s mindset during three different stages: rising star, established professional, and final years. His playing evolved over his career, but an enduring concern with directness of expression, achieved by way of absolute clarity of thought and action, seems evident. His affinity for these ideals makes sense, given jazz’s requirement to generate one’s own music in the moment.

As a classically trained musician who recently began formal study of jazz and improvisation, I have been struck by the lessons in personal responsibility I have learned. In brief, if I do not come up with my own music to play, then I will have no music to play. I still fumble through chord changes and peck at notes that I know will probably fit, but do not really know how they will sound. My ideal, though, is to develop a level of aural and physical proficiency through which I can always hear internally first, and then execute with ease. In this way, I am most truly responsible for the music I am improvising.

What about classical musicians and our relationship with the scores we play? If we conceive of the possibilities along a continuum in which purely reacting to the directions in the score is on one end and expressing a carefully considered personal statement is on the other, how do we tend to define our responsibilities through our actions? Reflection upon Bill Evans’s wisdom has certainly moved me to expand my own aims as a musician—in the point of view I bring to a piece and in the mind-body connection for which I strive. Evans’s words suggest that he recognized the immense responsibilities and opportunities that music offers, and he chose to fully embrace them. His self-belief, patience, and commitment to process can inspire each of us to choose to be not merely a player of music, but an artist.

Some of My Favorite Bill Evans Tunes

Tunes Composed by Evans

“Re: Person I Knew”

The title of this tune is an anagram of the name Orrin Keepnews. Keepnews produced some of Evans’s albums.

“Very Early”

Evans wrote this tune during his undergraduate studies.

“Time Remembered”

Tunes Composed by Others

“Elsa” by Earl Zindars

Zindars was from Chicago.

“Nardis” by Miles Davis

According to one story, the title of this tune is a play on the words “an artist.” Supposedly, Miles and Bill were playing a gig, and someone requested a tune that disagreed with Bill’s sensibilities. He rejected the request, stating that he wouldn’t play such music because he’s “an artist.”

Bibliography

Bill Evans/Time Remembered: The Life and Music of Bill Evans. 84 min. Produced and directed by Bruce Spiegel, 2015.

Crow, Bill. Jazz Anecdotes: Second Time Around. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Evans, Bill. “Improvisation in Jazz.” Liner notes to Kind of Blue, by Miles Davis. CD, Columbia 64935.

Lees, Gene. Meet Me at Jim and Andy’s: Jazz Musicians and Their World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Pettinger, Peter. Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Scott, Bill. Interview by Win Hinkle. Letter from Evans 1, no. 4 (March/April 1990): 3-5.

The Universal Mind of Bill Evans: The Creative Process and Self-Teaching. 45 min. Rhapsody Films, 1966.

Werner, Kenny. Kenny Werner on Meeting Bill Evans – What He Practiced… How to Play Jazz Lesson. Interview by Dave Schroeder. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cB283JLBFuM.

Zindars, Earl. Interview by Win Hinkle. Letter from Evans 5, no. 1 (Fall 1993): 18-21.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of the Chicago Flute Club Pipeline.