Over the past year or so, I noticed that there are certain pieces of musical advice that I tend to favor when helping students develop their playing. I also observed that I share this same advice with students of all skill levels, from beginner to advanced. Needless to say, I have made many a joke about sounding like a broken record. The fact is, though, that these bits of musical wisdom are incredibly powerful problem-solving tools. Thus, I share here my ten favorite pieces of musical advice, some of which were imparted by my teachers, and some of which I encountered via other sources out in the world. I hope you enjoy and benefit from this information, which for me has been a testament to the lasting positive impact a skilled mentor can effect in a musician’s life.

Advice from My Teachers

- The body learns more slowly than the mind.

One challenge of learning an instrument is the gap that can exist between intellectual understanding and physical capability. The above statement is a comforting reminder during those times when one is not yet able to produce on the instrument the ideals in one’s head. Proceed with mindful practice, and trust that it will enable you to close the gap.

- Listen to and draw inspiration from the masters.

One of my teachers often incorporated listening to recordings into lesson time. Whenever doing so, he reacted to these exemplary performances with such awe and admiration that one could not help but share in his excitement. Time and again, he modelled how to listen analytically and then strive for a similar level of excellence, which was a valuable lesson in itself.

- Problems of technique are almost always problems of rhythm. The problem of rhythm is almost always that you are rushing.

Whenever my finger technique falters, I rely upon this wisdom to solve the problem. I turn on a metronome and vocalize the rhythm while walking or clapping the pulse. I often workshop the passage even further by articulating the rhythms on a single pitch on the flute. Then, I return to the music as written and focus intently on pulse and rhythm as I play through the material. Steady, solid time organizes the movements of the fingers.

- If there is no time for space, you cannot practice space.

This advice is useful for learning to speed up articulated passages. Spaces between notes may work at slower tempos. As speed increases, however, these spaces can become a problem as there is less time to include them. Practice the material in a connected manner across all tempos, and notice how doing so facilitates the building of speed.

- Everything you need to know about playing the flute is in the first ten pages of the Taffanel/Gaubert (Complete Flute Method).

There is a small handful of fundamental techniques necessary for successful flute playing. It takes a lifetime of study to master these skills. Greatness in playing follows from devotion to continuous, incremental refinement.

Advice I Read, Heard in a Class, or Encountered in a Video

- Short notes lead to long notes.

This concept provides a starting point from which to analyze the directional organization of a musical passage. A notion of where a note or group of notes is going helps make sense of the material, which in turn, facilitates the execution of it. Understanding the momentum of a passage also informs choices on where to breathe.

- “Control the tongue with the stimulus of speech (rather than by physical manipulation). The tools of speech are psychological, not physiological.” Arnold Jacobs, quoted in Nelson, Bruce, comp. Also Sprach Arnold Jacobs: A Developmental Guide for Brass Wind Musicians. Mindelheim, Ger.: Polymnia Press, 2006. p. 55.

Tubist Arnold Jacobs advocated the use of simple syllables to direct the tongue for articulation, as opposed to striving to manage physical minutiae through sensory analysis. In fact, he contends that we are not adequately capable of feeling the positions of the tongue in the mouth anyhow. Some syllables he recommends are “tAH” and “tHO” (pronounced like “toe,” not “though”). Used in combination with a steadily moving airstream, this speech-based approach to articulation is wonderfully simple and effective.

René Magritte. The Discovery of Fire, 1935.

- I don’t have better tuning than anybody else. I just adjust more quickly.

If my memory is correct, I first encountered this purported remark by violinist Jascha Heifetz in a video segment on Classic Arts Showcase. Much to my disappointment, I have never been able to relocate that clip, though other sources attribute similar statements to Heifetz as well (see, for instance, here and the podcast/transcript available here). Be it intonation or some other aspect of playing, Heifetz is speaking to the value of two particular musical skills, 1) self-listening and 2) flexibility. Playing well is not about starting out perfectly and then somehow avoiding slipping out of that space. Rather, it is an active process of listening and responding. Developing a keen ear for one’s own sound and the flexibility to make any desired changes to that sound on the spot are the tools one needs to excel in this process.

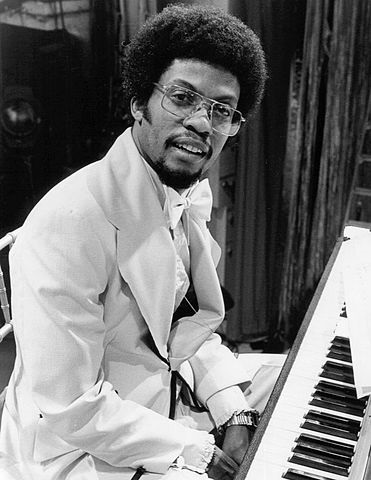

- “The reason that you have such a hard time playing fast is because you’ve never heard yourself play fast.” –Herbie Hancock quoting Donald Byrd (From the “Donald Byrd’s Secret to Speed” portion of the “Rhythmic Musicianship” video from the Herbie Hancock Teaches Jazz class available at MasterClass Online Classes (www.masterclass.com))

As Herbie Hancock learned from Donald Byrd, part of the barrier to getting comfortable with playing fast is not having heard oneself do so. To experience hearing oneself play fast, Hancock recommends jotting down some solo choruses over the changes for a quick-moving tune. The musician should sketch out whatever she hears internally and not concern herself with whether she can play the imagined materials. After notating the choruses, the musician should practice them, not for the purpose of attaining mastery, but to “get it a little bit under your fingers,” as Hancock recalls Byrd putting it.

For the improvising musician, the challenge with playing fast could encompass the physical act of execution, the mental element of imagining quick-paced materials on the spot, or the psychological necessity of having sufficient confidence in one’s abilities as a player. Via pre-planning/notation, followed by loose practice at the instrument, Hancock’s method addresses all of these angles. Working through the process, the musician hears herself play fast.

- “A genius is the one most like himself.” —Thelonious Monk

“I like what Picasso said. He said, don’t worry about trying to develop your own voice. Just try to draw a perfect circle. And, it’s impossible, and the flaws—that’s your voice.” —Kurt Rosenwinkel, remarking on Picasso

Since I was unable to settle on a single quote for no. 10 (and my commentary on no. 9 grew longer than I intended!), I will keep this brief.

Be yourself. Appreciate yourself. Open yourself to appreciating and supporting others for being themselves, even if their artistic voices and preferences are different from yours.

Pablo Picasso. The Old Guitarist, late 1903-1904. The Art Institute of Chicago.