In the fall of 2017, per the recommendation of a friend, I enrolled in Learning How to Learn: Powerful mental tools to help you master tough subjects, an online course available for free at www.coursera.org. I thoroughly enjoyed working through the materials and learning from the wonderful instructors, Dr. Barbara Oakley and Dr. Terrence Sejnowski. The experience prompted me to examine my study habits, and make adjustments or form new ones. In addition, I developed more patience with myself as I worked on new endeavors.

During the current pandemic, many of us have been learning new things—how to keep ourselves and others safe, how to continue the schooling of children, and how to carry on in our professions if somehow possible. The increased time at home has encouraged many people to pursue a new learning project as a source of entertainment. Experimenting with different recipes for the same dish has sounded particularly fun to me, though I admit that I have not tried doing so myself yet.

Reflecting on what skill building I might do during this time, I recalled that there is a beginner-level Learning How to Learn course titled Learning How to Learn for Youth (henceforth, LHTLY), which is also available for free on Coursera. Dr. Oakley and Dr. Sejnowski lead this course as well, along with Greg Hammons, another great instructor. I decided to enroll, and although I was unsure about what to expect in terms of presentation style, I found LHTLY to be a course with appeal for all ages. In my case, it served as an incredibly helpful review of concepts I encountered previously. Moreover, it instilled in me a desire to dive deeper into the fundamentals of a couple subjects I have been pursuing on the side (more on the significance of fundamentals later).

In the spirit of learning by teaching, one of the memory strategies mentioned in LHTLY, I decided to write this review so as to solidify my grasp of the course materials while sharing that knowledge with others. I overview the highlights of three areas of content—brain basics, learning strategies, and keys to success. Along the way, I provide relevant examples in music, the field in which I am a professional. It is my hope that this blog post will inspire you to take the course yourself and enhance your learning capabilities.

A Couple Brain Basics

1. Off-the-Clock Learning

Learning involves thinking in new ways and making new connections in the brain. It requires periods of concentrated study. That said, when we step away from our learning materials and turn our attention to another activity, be it studying a different problem or enjoying some leisure, the brain continues to work on the previous task. This learning that takes place in the brain while we are seemingly “off the clock” with a given matter is an integral part of the skill-building process.

2. Brain Links

Study and practice change the brain. Brain links form, which group together information and enhance our ability to work with the knowledge we have gained. The quality of your study affects the strength of your brain links. In addition, the more complex the information, the longer the brain link. As a result of their commitment to learning, masters in a field possess strong brain links of various sizes.

Three Essential Learning Strategies

1. The Pomodoro Technique

The Pomodoro Technique is an excellent strategy for motivating yourself to accomplish some high-quality study or practice. To “do a pomodoro,” set a timer for twenty-five minutes, and eliminate the possibility for distractions in your work environment (for example, silence your cell phone). Then, start the timer, and work solely on your chosen learning activity. Once the timer goes off, stop working, and enjoy a reward activity for five to ten minutes. I particularly like to do a bit of light exercise during my reward periods.

The Pomodoro Technique is an effective learning strategy for multiple reasons. For one, the relaxation component allows the brain an opportunity for the aforementioned off-the-clock learning, and quite literally in this case! Furthermore, the presence of a reward generates a willingness to complete a study session. Plus, since many study projects cannot be completed in a single twenty-five-minute session, the Pomodoro Technique fosters an appreciation for the process of learning itself.

Musical Example: Celebrated tubist and music pedagogue Arnold Jacobs advocated pomodoro-like practice. Consider these remarks, which suggest a divide-and-conquer approach: “Efficiency in learning involves short periods (say 20 minutes) of heavy concentration. In practice, it is not necessary to start at the beginning of a piece and play all the way to the end. Start with the spots that are most difficult for you” (Nelson 2006, 63).

Or, how about this passage, in which he prescribes a specific practice goal and recommends a twenty-minute time limit once again: “When playing alone, there is a tendency to substitute matching efforts for matching sounds. Concentrate on ease of playing. Practice one piece and see how easy you can make it. Don’t worry about other factors for a 15 or 20-minute session” (Ibid., 61).

2. Regular Practice

Although the Pomodoro Technique may be unfamiliar to some, the importance of studying on a regular basis likely is not. As LHTLY explains, repeated engagement with material over the course of an extended period supports the ability to remember those items for a long time. The accumulation of reliable knowledge and skill is necessary to performing with ease and expertise in a subject area.

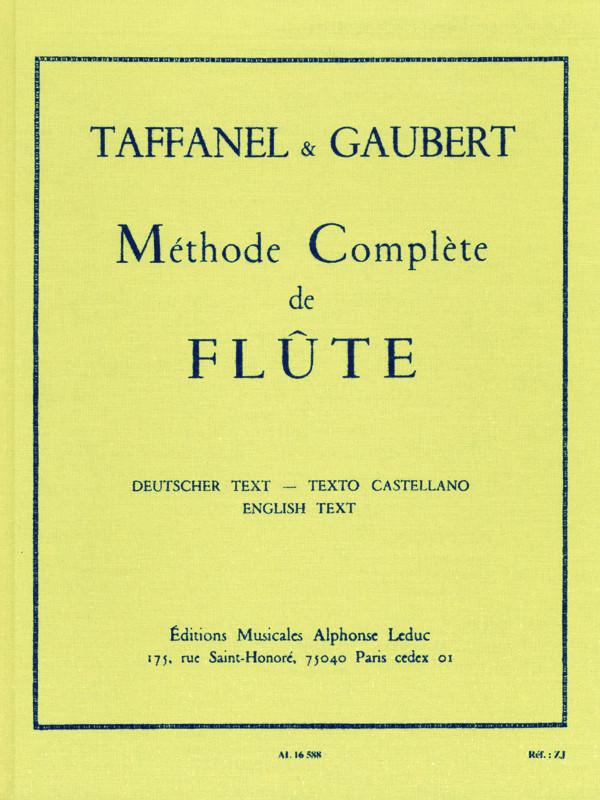

Musical Example: In the opening pages of Méthode complète de flûte, Paul Taffanel and Philippe Gaubert provide a practice schedule for the week. The chart includes a plan for every day except Sunday, which is absent from the list. It is heartening to see that these two monumental figures in flute history apparently believed in balancing a week of consistent, well-planned study with a full day of rest.

Taffanel and Gaubert divide the practice regimen for each day into three parts: 1) scales, 2) other fundamentals (such as arpeggios and sustained notes), and 3) an alternation between etudes and pieces from one day to the next. Each of the three components of a day’s practice could be a single pomodoro, or if the flutist is feeling more ambitious, two!

3. Recall

As you study, challenge yourself to recall the materials you are learning. By testing your ability to, for instance, play a few phrases of a piece without looking at the music, you are working on not only memory but also understanding.

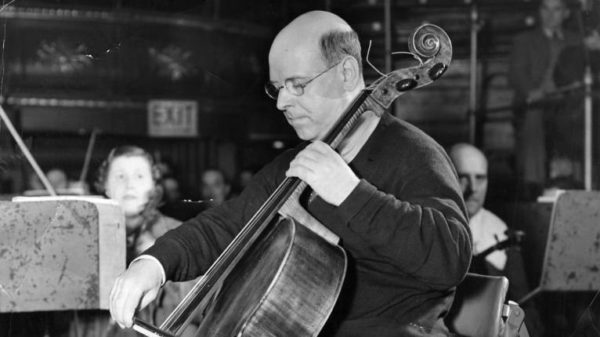

Musical Example: In a previous blog post about flutist Bernard Goldberg, I recount some wisdom imparted by one of his mentors, cellist Pablo Casals: “Try to memorize as quickly as possible so you find the music behind the ink.” Recall is the performer’s stepping-stone to building an interpretation of the music’s message.

Keys to Learning Success

1. Be open to the possibility of broadening your skill set, and in turn, the value you can bring to others. For example, a flutist who pursues on the side her interest in piano playing may eventually be able to accompany her students. Regular work with an accompanist is a tremendous asset to the developing musician.

2. Embrace fundamentals as they will help you establish a strong foundation on which to build. Through such study, you might notice connections with previously acquired knowledge and skills, connections which can facilitate the learning of the new material. For instance, a classically trained musician who would like to play jazz would do well to start by learning to read some of the more commonly used chord/scale symbols in that music. These chords and scales and the ones typically mastered for classical playing share many similarities.

3. Allow for course corrections. We learn by doing. If you realize that you understood something incorrectly, or conclude that you could do a task in a different, better way, allow yourself to make a change. A former professor of mine once told me that after reading the first two chapters of his dissertation draft, he decided to throw all those materials in the trash and start over again. Given that he ultimately became a beloved professor at a major university, one might say that subsequent events were still able to go quite well for him. Do not worry, though—decisions to correct course need not all be so dramatic!

What LHTLY Offers Us All

We are all learners. By sharing insights on how the brain works and what approaches to study are particularly effective, LHTLY offers us all the possibility of improving our efforts to learn. In response to understanding just a little bit about how the brain handles and retains information, we can choose to adopt new habits for how we approach our studies and even life in general. Sleep, exercise, and nutrition all play a role in our ability to learn.

The three learning strategies I highlight in this post—the Pomodoro Technique, regular practice, and recall—are ones I consider essential to developing some level of mastery with whatever subject matter you are pursuing. Take note that the course presents multiple other tools and tricks, including the playful memory palace technique and the use of metaphor.

As for the keys to learning success, we can take this advice as both encouragement and a call to action. Find a teacher or reliable online sources, and broaden your horizons. As you take on a new learning project or up your game with a current one, have patience with yourself as you dig into fundamentals. Through persistence, things will get easier, and remember, mistakes will be part of the journey.

What if you are already a successful learner in several subject areas but have been avoiding taking on a dream project out of fear? Get to learning on a small scale, say five to ten minutes a day, five days a week. Let the process unfold for a few weeks, and see what happens. You might decide the project is not for you, or you might decide to change your mind—you truly have the capability to do so.

Nelson, Bruce, comp. Also Sprach Arnold Jacobs: A Developmental Guide for Brass Wind Musicians. Mindelheim, Ger.: Polymnia Press, 2006.