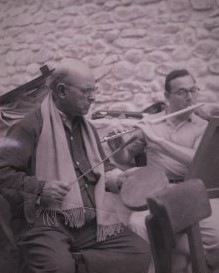

My third private lesson with Bernard Goldberg was on 29 April 2017. This lesson was the last he taught during his final teaching tour of the Midwest. I prepared a variety of lyrical selections for our meeting. The topic of artistry came to the fore.

A central theme of the lesson was developing the inner musical vision and learning to transmit that inner vision outward. Bernie spoke on the value of playing from memory as his mentor the renowned cellist Pablo Casals (1876-1973) explained it: “Try to memorize as quickly as possible so you find the music behind the ink.” Bernie’s suggestion to play from memory may seem, at first, to be primarily concerned with interpretation. By introducing the subject of memory, though, he brought ear training into the lesson. As I attempted to play some of my repertoire from memory, he focused on tuning by way of singing the scalar relationships within the music. He emphasized the importance of training the ear to be keenly aware of one’s own playing whenever engaged with the instrument. There is the way the flute is built, and there is the way the music is built, as he put it. Through the study of solfège, together with an increased capacity for self-listening, the flutist can bring her flute playing into closer proximity with the music’s construction, thereby improving intonation.

Bernie presented a couple general guidelines for intonation. First, the flutist must aim to match a given pitch across all its occurrences within a phrase. For example, if a phrase contains multiple middle Ds, the tuning of these Ds should be consistent. Likewise, the sound of the interval from major scale degree four to five should match the sound of the interval from major scale degree one to two, as both intervals are the same distance of movement (a whole step). In sum, Bernie’s approach to tuning centers on teaching the “inner ear.” The inner ear then provides the model to which the flutist adjusts in response to what she hears in her playing.

During the lesson, Bernie also conveyed the value of doing the necessary research to express the story of the music. For instance, in discussing the articulation for “The Moon Over the Ruined Castle” as it appears in Marcel Moyse’s Tone Development Through Interpretationbook, he noted the prevalence of resonant percussion instruments and plucked strings in traditional Japanese music. Given Moyse’s notation of the melody—slurs spanning across notes over which there are staccato marks—Bernie’s comments on the sound world of Japanese music offer a thought-provoking conception for shaping each note. The idea of resonance or of a pluck draws one into thinking about not only note beginnings but also middles and ends. Bernie also laughingly remarked that he gave considerable thought to the question of how to describe the atmosphere of this tune in words, but ultimately concluded that simply thinking of an old castle in the moonlight worked best.

Bernie’s dedication to his craft extended beyond an intellectual knowledge of his musical material. He sought to embody it. The anticipatory breath at the start of the music was of critical importance to him in this realm. As I initiated a piece, he coached me on taking an anticipatory breath in the music’s tempo—a breath that gave him an awareness that my body and whole spirit were in that time. I continue to imagine his voice in my head helping me in this way, and of course, in many others.

Sometimes when Bernie was looking back on his career, he would say, “I gave them everything.” Whenever he spoke in this way, I always imagined all the hours of practice and study and all his efforts to pour his emotions into his playing. Reflecting upon his teaching of the anticipatory breath, I came to understand that the “everything” Bernie spoke of encompassed far more than mind, heart, and skill on the flute. It was every ounce of his being. Perhaps the biggest artistic lesson is learning how to commit yourself to embodying all you can possibly offer.

Thank you, Bernie.